Wednesday, 19 October 2011

The science of whisky

You would not expect the scent of whisky to waft from a chemistry lab. You certainly wouldn’t hope to smell it around working scientists. But with 300 detectable chemical compounds, whisky is more complex than human blood. It is made by the standard scientific technique of distillation and it has a very scientific life.

This life begins as a simple beer. To make whisky, first, malt some barley. Next, add yeast, and let it devour the sugars released by the malted barley. This sweet fuel is energy for the yeast to produce alcohol by fermentation. Together, the alcohol, yeast and sticky barley form the beery “wash”.

Scottish monks were making whisky in the 12th century, by condensing the vapours of boiled “wash” to drink. This distilled spirit was named uisge beatha, the water of life. It was clear like vodka, twice as strong, and drunk without adulteration. Darren Rook of http://thewhiskyguy.co.uk explains, “The Scottish monks learned the method of whisky making from European counterparts who called the spirit aqua vitae – a little like scientists share their methods today.”

In the 18th century someone discovered something magical: if you pour this strong, clear, distilled alcohol into a large barrel and leave it a while, you will discover an amber, smooth drink that seems to cleanse the soul. Now, with modern techniques of mass spectrometry and chromatography, scientists can explain the magic that makes the whisky we know.

Some chemical compounds sneak in at birth. The first stage of whisky-making, malting, requires fire to dry the barley. Peat is one fuel for this fire, and peat contains phenols. These aromatic hydrocarbons produce the rich, smoky flavours of whiskies made in peat-fired distilleries like those on the small Scottish island of Islay. When you sip an Islay whisky, you can almost feel the peaty smoke fill your mouth.

Distilling adds chemical fire to the wash. It captures the strong, burning ethanol, but also the buttery diketone, diacetyl, and the fruity acetals. Distillation also produces fusel oils. In small quantities, these higher-order, oily alcohols round out a whisky, giving it body. In excess, fusel oils are toxic. The stillman who brings the whisky through this adolescence is a Goldilocks figure, cutting off the distillation at precisely the point where the concentration of fusel oils is just right.

And so we have a teenage spirit, grown up from its babyish beginnings in a warm bath. What our 12th century monks did not know is that uisge beatha is not the end game. Place the young spirit in a wooden womb and something really comes to life. After three years or more in an oak cask, the water of life is reborn.

“We do not know exactly what happens in the cask, it is still a mystery that science is yet to fully understand,” says Professor Paul Hughes, Director of the International Centre for Brewing & Distilling, Edinburgh. What the Centre’s scientists do know is that chemical compounds in the oak enrich and transform the spirit.

Tannin, which makes tea brown, gives whisky its golden glow. Oak lactones also mingle in, giving a hint of sweet coconut. The carbon lining of charred whisky helps to release vanillin from the oak. The active carbon filters out undesirable substances like sulphur that cause an eggy taste. Gaps and pores in the cask’s wood let in air. Gently, gently, this air oxidises the alcohols, breathing new life into the spirit. Ethanol reacts with acids during this maturation process, giving rise to zesty esters – more commonly found in pear drops.

The final result is an aged concoction so loved worldwide that in 2010 Scotland’s whisky exports earned the UK £109 a second. That’s a staggering 1060 million bottles sold. And while the chemistry of whisky-making stops at bottling, the science is far from over. Whisky is made for tasting, not examination under the spectrometer. The human brain is possibly the most remarkable detector of all.

The moment whisky enters the mouth, our salivary glands spring into action and one little sip sloshes around ten thousand taste buds. Volatile compounds like the esters travel up the nasal passages. The brain’s olfactory and gustatory areas (for sensing smell and taste) light up. Our remarkable minds discover and describe flavours that are often unbelievable. Members of the Scotch Malt Whisky Society (SMWS) sometimes describe the taste of iodine to SMWS Ambassador Craig Johnstone, although, “there is no iodine in the whisky. But aromas are very strong triggers for memories and phenols do give an antiseptic smell to whiskies, much like iodine in old antiseptics.”

As the last traces of a whisky die from the tongue, its long and complex life ends. It is a life of evolution and metamorphosis, of meetings between chemicals with long and complicated names. But what a life.

Sunday, 25 September 2011

The house of pain

I think I’ve experienced quite a lot of pain. I’ve had ballet teachers sit on my back to force me deeper into the splits; deep tissue massage on torn hamstrings. I’ve danced en pointe, with 40N/cm2 of force going through my toes, until they have bled. I’ve trapped a nerve in my hip and been woken up at 3am with cramp that feels like my left foot is trying to break itself in half. It once happened in the kitchen and I reached for the bread knife.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve had headaches nearly every day. Until my early teens I thought this was normal – low level pain in your head is just what happens from being alive. But once I became old enough to articulate my perceptions, I realised this frequency of pain would never be tolerated by someone who hadn’t experienced it all their life. I guess something chronic becomes normal after a while.

Once I had suffered three “ice pick” headaches age 16, I finally went to the doctor. Ice pick headaches do exactly what they say on the proverbial tin: they feel like a cruel, demented tormentor is driving an ice pick into my brain. They are excruciating, but mercifully last only three seconds (on average, for me). I reassure myself that it can’t be as painful as the contractions I might, one day, experience during labour. But I don’t know what labour feels like, so last night I asked people who do know how it compares to severe cramp, to create some sort of gauge.

But how do I know what it feels like to have an ice pick driven into my brain, really? Is what I feel as an ice pick being driven into my brain the same as what “Mike” in this case study feels? How do my ice pick headaches compare to the cluster headaches, nicknamed “suicide headaches”, that my friend Dawn endures? What is our language for comparing pain? Is it just comparing one type of pain to the other, like I tried to do on Twitter?

The Wellcome Trust-funded London Pain Consortium, which I sincerely hope has the internal name “House of Pain” and a mandatory afternoon coffee break where researchers Jump Around to escape the post-lunch slump, is looking into it. They will use hi-res fMRI and diffusion tractography imaging techniques to look at what is happening in the brain, both what it’s doing and where, during induced and existing pain. Though, rather than shoving a sharp, pointed object up someone’s nose, they will be using extract of chilli peppers to cause pain.

I should say that I’ve distilled the above explanation of their research from a rather jargon-filled summary and as I’m not a neuroscientist or the best science writer, I might not have done this very well. So two things: please correct me in the comments, and, London Pain Consortium: please put some decent public information on your website. Mun-Keat Looi wrote a feature that looks at their chronic pain research on the Wellcome Trust’s website and Barry Gibb produced this video for the same. But they shouldn’t rely on external science communicators to explain their work to a large swathe of the public (one fifth of Europeans suffer chronic pain) who are, like me, very interested to know what the House of Pain is getting down to.

*I addressed this question to “mothers” and later regretted it. I realise that women who now have children are not the only ones to have experienced labour contractions. They occur during abortion and miscarriage too. Twitter does not allow for much expansion and I wanted to address my tweet to someone to increase the chance of it being noticed and answered, but I did not mean to exclude anyone with first-hand experience of this kind of pain.

Sunday, 7 August 2011

I Love You, Waterloo Bridge

Waterloo Bridge is the king of London bridges. Why is it masculine? I'm not really sure. But it's strong, and comforting, and it makes me feel safe. Like everything's okay. (Though maybe that's more indicative of my relationship with men.)

I moved to London for university eight years ago, and never wanted to go back to the tiny town in Dorset where I spent the first eighteen years of my life. Broadstone is sweet, and peaceful, but it's not me. I enjoy a short visit to my parents a few times a year, but when the train pulls in to Waterloo Station from its journey across the south coast, I feel a sense of relief. As my footsteps fall over Waterloo Bridge, I feel like I'm coming home. Like everything's okay.

Wendy Cope has written a poem that reflects upon this magnificent bridge better than my words can:

After The Lunch

On Waterloo Bridge where we said our goodbyes,

the weather conditions bring tears to my eyes.

I wipe them away with a black woolly glove

And try not to notice I've fallen in love

On Waterloo Bridge I am trying to think:

This is nothing. you're high on the charm and the drink.

But the juke-box inside me is playing a song

That says something different. And when was it wrong?

On Waterloo Bridge with the wind in my hair

I am tempted to skip. You're a fool. I don't care.

the head does its best but the heart is the boss-

I admit it before I am halfway across

Wendy Cope

Whenever I'm halfway across Waterloo Bridge, I snap a photo. The view from Waterloo Bridge showcases the best of London's landmarks, and it seems to change every time I cross it. These photos are not very good, but they're a chronicle of my homecoming and I hope the different moods show why I cannot get enough of the king of bridges.

Tuesday, 26 July 2011

Saying goodbye

On Saturday afternoon I was jolted back to Thursday 19th April 2007. The night my eldest brother was found dead in a corridor next to two empty bottles of vodka. That night, I drank whisky in the Hawley Arms in the presence of Amy Winehouse, who died on Saturday. Not knowing he was dead. Not knowing that four years later she would succumb to the same addiction Paul did. Not knowing that the same chemical I was using for enjoyment had killed my brother in massive amounts. Not knowing I had missed the chance to see him just one more time. Just once more. One more time and that’s it.

It seems crass to use the death of one person to bring attention to your own grief. I do not mean to do this. I mean to reflect on something I have shared with few people and to give tribute to a man whose loss marks my soul. Who introduced me to music and told me about our Irish ancestors, who was the big brother who’d beat you up if you were mean to me in the playground.

Paul Christopher Maddocks was born in 1969 to my Mum and her first husband. I won’t pretend the loss of a brother is the same as the loss of your first, beloved son. Paul was 8lb 12oz, and upside down; my Mum 7 stone 12lb and without the offer of a Caesarean section. He nearly killed her then and he nearly killed her when he died. The shock of bereavement slammed her adrenal glands. She stopped producing the hormone that regulates salt levels. But the doctors didn’t know that. After a week of suspected stomach flu, when her body ridded itself of every drop of water to rebalance the salt in her blood, she went into “Addisonian crisis”. Her vital organs were shutting down, breaking like her heart had on that day in April. The vicar who visited her says he’s seen people that left hospital in a coffin who had looked better than she did.

Mama's gonna keep you right here under her wing / She won't let you fly but she might let you sing / Mama will keep baby cosy and warm.

After Paul’s birth, Mum swore “never again”. She went on to have four more children. She always wanted a girl and along I came in 1985. Paul was 16 and already drinking too much. I don’t believe addiction is just a disease on its own, I don’t think people abuse alcohol for no underlying reason. He was always searching for something, for who he was, what he was.

Paul's dad left my Mum when he was just five, a disruption that began a lifetime of searching for an identity. He was obsessed with his heritage. A few years before he died I met him in Farringdon, to vainly hunt for the death certificate of our Irish-born great-grandmother in the Family Records Centre. Years after our grandmother’s death he discovered that she, an illegitimate child of World War One, had been sent to a nunnery when she was an infant. Her nun’s name? Sister Mary Louise. The connection must be coincidence as not one family member knew of this before Paul. I’m forever grateful he revealed this unknown link between me and my half-Irish Gran.

Where Lagan stream sings lullaby / There blows a lily fair / The twilight gleam is in her eye / The night is on her hair

Our Irish ancestry fired Paul’s imagination and his writing, which he tried to make his living, but failed. Each knockback from a publisher or film producer would always turn him back to drink. The family research inspired poems about Irish lords and kings, the pseudonym Pól Mac Madóg and beautiful Celtic drawings in his notebook that I pore over every time I’m reminded of him.

Someday you will find me /Caught beneath the landslide / In a champagne supernova in the sky

When I was 16, on Christmas morning, Paul told me his ex-girlfriend was pregnant. Just like that, like I was supposed to already know. I didn’t. I’ve never met Billy. Paul didn't meet him much either.

Another Christmas we had to lock all the alcohol in the shed because Paul had crashed again. It was always a cycle of recovery, remission and relapse. Nothing we did could help him for long. Like Amy Winehouse, and all the world’s addicts, celebrity or not, he just seemed unable to resist the demons of self-destruction.

In the last few years of his life, Paul studied music on South Uist, an island in the Outer Hebrides. It was something of a joke to run away to the Hebrides, but he actually did it. But he couldn’t outrun those demons. He was clean for a year before the drinking started again. By January 2007, he knew he had to get help once more and we met him at Euston Station at the end of a two-day long journey from the furthest reaches of Scotland. For him, a two-day long binge. He was unconscious when the train pulled in.

Wake from your sleep / The drying of your tears/ Today we escape, we escape

At UCLH he begged to stay with me. Through tears of shame, “I want to stay with Louise.” You might think I cried too, but I was numb with fear and worry that this was the worst he’d ever been. And filled with a cold fury that my eldest brother, the one who called to chat about bands and books, the one I talked to about politics and life and what on earth is the Daily Mail banging on about now, was poisoning himself with alcohol and he was going to die and it wasn’t fair.

This is a sad fucking song / You'll be lucky if I don't bust out crying

We took him to stay with Mum. After three months, he had kicked his habits. Drink, fags, long shaggy hair all gone. A new man thanks to the bloody-mindedness of the mother who survived him being ripped out of her feet first. The mother who would later turn away from death, and the oblivion from grief that she could so easily have embraced, through sheer will to protect her family from another death.

Oh mother, I can feel the soil falling over my head / See, the sea wants to take me / The knife wants to slit me / Do you think you can help me?

But when Paul left Mum’s home for his new life, he broke like a glass bottle smashed against a wall. The thing about addiction is that it has to be the addict who is strong. Family and friends can only form a barrier to those demons for so long. Faced with being on his own, he folded. And drank. And drank. And drank.

A week before Paul died, I went on holiday. I deliberated phoning him. I knew he was in a terrible state. The hour-long, rambling phone calls. The desperation in his cracking voice, his throat raw from neat vodka. Every time I said goodbye I wondered if I’d ever see him for one last hug. A farewell kiss. One last listen to Half Man Half Biscuit.

What could I do? Cancel my holiday and fly to his side just in case? One final effort to make him give up the ghost that haunted him, the ghost of obliteration?

When they found your body / Giant X's on your eyes

A week later I was in the pub. A week and a day later the phone call from my Mum, “He’s gone. He’s gone.” I realised I had said my final goodbye, two weeks before, the last time we spoke on the phone. He died, and a bit of me died too. And it still dies again and again, every time I realise I will never get to see him that one last time.

We only said goodbye with words / I died a 100 times

Sunday, 19 June 2011

Thirty Odd Years Ago

My sixth summer saw me fatherless and trying to work the world out, unconscious to the gravity of each, neither weighed me down.

I thought Queen morphed into Abba, variations on a theme of Mamma Mia, for a while; then, that there were just three teams in League Division One.

The end of World War Two had been just thirty years before and my Grandad would stomp round to use the phone. He never knocked.

School was Gothic, sometimes vomit spoilt the day. Church would always hold my soul, television grabbed my bones.

Football sticker albums taught me where things were and Celtic’s not a place, and things grow on nun’s noses. All I’ll recall of Sister Liam is her face, and Sister Aloysius held me both in fear and thrall.

I had a little book of saints, treasured art, that ended in the toilet; as I say, the downfall of the Nazis had been thirty years before.

I found a dead mouse in the garden, which upset me. I understood for the first time nothing lasts forever.

Paul Maddocks

1969-2007

Friday, 3 June 2011

At the fund raining ball

On the sunbed, dead

The picture in the local mag had said,

'At the fund raining ball, (sic.)

Local lovely Debbie, forty.'

Poor Debbie.

Saturday, 14 May 2011

Dance, dance, dance

Ballet age 4 is all about good toes, naughty toes, and various mimes that transport you far away from being a four-year-old with bouncing blonde curls. Once upon a time I was a naughty imp stealing apples from a garden, or a graceful swan soaring high. Sometimes, us little ballerinas had to be a witch who drinks a deadly potion, but I was scared that pretending to die meant dying in real life, so I never was the witch.

Growing up meant more serious exercises: tendus, fondues (dancing cheeses?!), grand battements and jetés. Age 11, I was selected for a special advanced class for students with "distinction". I wore pointe shoes for the very first time. Dancing en pointe is painful, thrilling, and so very grown up. Though the lasting legacy is that I have baby-sized feet: at 5 feet 9 inches tall I wear size 4 shoes, because dancing on your tippy-toes four days a week during puberty doesn't allow for much growth.

Being an adolescent ballet dancer is tough. Suddenly, you're too big, your legs are these great long levers that you're supposed to lift at impossible angles to your protesting body. Training for my second major exam, I tore my left hamstring, and six months later, the right. Thus ended my career as a ballerina. (Although it was always clear I would be too tall. Even Darcey Bussell, a "tall" ballerina, is only 5 feet 7. And anyway, I was too "clever" to go into dance, a career in science beckoned...)

The injuries, and subsequent back problems, were tough, frustrating, but made be want to dance even more. To overcome my injuries would be a great achievement. Age 17, I won the Senior Prize for Achievement at the renamed Poole Academy of Dance. My trophy was a treasure for one year, and then I had to give it back, and leave for University College London.

UCL owns the Bloomsbury Theatre and as such has thriving arts societies: Dance, Drama, Stage Crew, Musicals. I joined Dance. Going to university coincided with, or perhaps forced, a darker side of me. Out went the blonde curls, in came jet black, poker straight locks and gothic tendencies. My studies of the history of madness led me to learn of the mediaeval witch-hunts and then I thought: why not, finally, dance the witch? So in 2005 I choreographed Sabat, named after the witch's gathering, for the UCLU Dance Society show. If I thought dancing en pointe was grown up, conceiving and birthing this expression of my imagination was almost ancient. Three ballet dancers and five tap dancers envoke the persecution of women that was rife for three hundred years.

It's six years since I performed that dance. Five years since I went to a ballet class. Boyfriends, work and apathy get in the way, don't they? But it's no excuse. So on the 117th anniversary of game-changing choreographer Martha Graham's birth, I went back to the barre, back to ballet class. Today I can hardly walk as my muscles scream out in protest once again. But I'm not going to stop. Ballet is not just in my bones, but in my ligaments, my tendons and my muscles. And since three years ago, tattooed into my skin.

I'd love to hear about anyone else's experiences of going back to dance as an adult, or even starting from scratch. I'm going to adult classes at the Central School of Ballet because it's just round the corner from my new office. But there are loads more studios around London offering classes for grown-ups: Danceworks, City Academy and Expressions to name a few. Many more across the country, I'm sure.

Sunday, 24 April 2011

Why I went to church today

I was thirteen when I marched downstairs one Sunday morning and presented my mother with a list of reasons why I didn't believe in God. She read them, offered a few standard placations, and never forced me go to church again (though she often pleaded). A small pivot in my evolution from child to adult. After that, I went to church only for religious holidays and too many funerals, but stayed mute for anything other than the hymns, and even then my churlish teenage mind refused to sing any words relating to the Holy Trinity.

But now I'm back and I'm singing my heart out. The reasons are many but mainly this: I am precisely twice thirteen years old, but the amount I've matured has far more than doubled. I've considered my family's religion and I've realised that the worth in normal, everyday Christianity is community. Going to church and singing about God does not betray my atheist beliefs, it does not bring me closer to Him but it does bring me closer to my family.

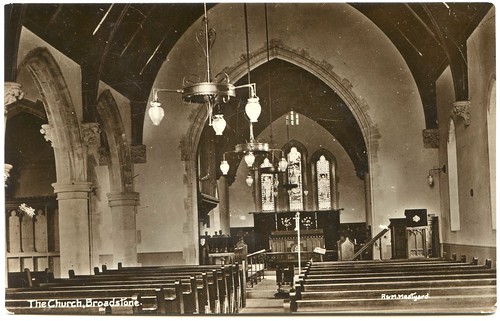

My parent's local church: St John's, Broadstone, Dorset. Real photo postcard by R & M Meatyard (date unknown). From alwyn_ladell on Flickr.

In a BHA survey last year, fewer than half the respondents who identified as Christian said they believed Jesus Christ was a real person who died, came back to life and was the son of God. Indeed my father, who goes to church every Sunday, confessed to me five years ago that he does not believe Jesus is the son of God. There are many similarly-minded people who go to church simply to meet other people, to enjoy a shared experience, or just as part of routine. We are creatures of habit, and sometimes the loss of something that has been with you all your life is too painful to bear. So Dad goes with Mum (who is less enlightened than he) every week to a beautiful building to sing and praise the wonders of life. The difference is Mum believes God made these bright and beautiful things; Dad thinks not. Does it really matter? Church brings them together, and today I'm together with them, and they're happy I'm there.

Last week, I even went to a church on my own, of my own volition. Four years ago my Catholic brother died. To mark this, I lit a candle in his memory and wrote him a song lyric in a book for prayers. Churches aren't just buildings of religion, they are anchors. I spent my grief there, rather than at home, or in an art gallery, or a pub, or anywhere else he identified with because there is a tradition of lighting candles in churches and it is comforting. A place to deposit my sadness and my loss, and then leave.

The words of Martin Rees on winning the Templeton Prize struck a chord with me: "

Thursday, 10 February 2011

The comfort of a chiropractor

I've been ill for a week, so my thoughts have naturally wandered to medicine. My drug of choice has been giant chocolate buttons. Not strictly a medicine, but the bright purple packaging, the crack of each button in my crunching teeth and the sweet sugar rush is so comforting. This reminds me of chiropractic: a questionable treatment, but in my experience, a big comfort.

Who loves the feeling of making their knuckles pop? This is what spinal adjustment, the technique chiropractors employ, feels like. This kind of immediate relief is very important for a teenager whose dreams of being a ballet dancer have just been ripped apart. I had no idea that chiropractic was founded on pseudo-science. Why would I? I grew up in a typical Daily Mail household where little was questioned. And would I have cared? Probably not. After weekly sessions of adjustment, massage and ultrasound treatment, I could dance again.

It was possibly, and probably, the more standard techniques of deep tissue massage and ultrasound that healed my aching body. A physio at the nearest hospital could have treated me in the same way. But Beth was a family friend and known in my local community. When my dad took me to a practitioner who had helped him, I felt cared for. My Dad was looking after me. During my sessions with Beth, I chatted about my university plans and she even helped me choose what to study.

Thursday, 27 January 2011

Undiluted spirit

The chemicals that are reaching your nose are a complex mixture, the culmination of distillation and years maturation. But they are not a fixed set, you can still alter and change the bouquet that greets your nose and so the flavour of the whisky simply by adding water. Adding water to whisky changes the concentration of alcohol and so increases the volatility of alcohol-soluble hydrophobic or long-chain compounds such as the fruity esters, increasing the fruity aspects of the whisky's flavour.

In contrast, smoky phenolics and roasted nut and cereal-flavoured nitrogen-containing compounds are water-soluble, and the volatility of these is reduced with water addition and so the smoky aspect of the whisky's flavour is reduced. However, the addition of ice reduces the temperature of the whisky and hence reduces the volatility of all the compounds, leading to a reduced aroma and a diminished taste.

Which is why you should never, never add ice to your single malt.

I've just bought an eye-watering Bruichladdich single cask whisky. Single cask means the whisky has come straight from the cask it's matured in, and not mixed with anything. This whisky is undiluted, so it's a whacking 66% alcohol. The whisky you buy in the shops or most bars is always watered down to make it more palatable to the average imbiber. It's ready-diluted, at around 40%. The beauty of my whisky (from the Scotch Malt Whisky Society) is that I can water down the neat spirit to suit my tastes, releasing those delicious flavour molecules as I wish. Or not, if I'm feeling particularly masochistic.

Cheers!

Wednesday, 26 January 2011

From Then On

From then on

It’ll always be different.

Quite apart from the pain

And the grief

And her room unchanged,

In the street

They’ll always be different;

From then on.

From then on

They’ll wonder at death,

But you’ll know.

They’ll ask you round;

If you don’t want to go,

Understand,

But still wonder at death;

From then on.

From then on

You’ll wish you could scream.

You carry emotions

From room to room

And they have small notion

Of gloom.

Every day’s a bad dream

From then on.

Paul Maddocks

26 January 1969 – 19 April 2007